In late September my PhD student Bill Ludt and I traveled to

the beautiful island of Tahiti to attend the 10th Indo Pacific Fish

Conference. This meeting takes place every four years and I have been

anticipating this trip since Bill and I went to the last meeting in Okinawa in

2013. I also knew that I couldn’t go all this way not to collect fishes. As

with other conferences in remote locales, and most field trips, it took a while

to get permits; we were lucky to get them a day before our planned travel began

(even though Bill had been working on them for more than a year).

Also joining us for part of the trip was LSU Biology

professor Brant Faircloth. Brant and I submitted a proposal to run a symposium

on fish systematics focusing on ultraconserved elements. Our session ultimately

became part of a half day symposium called ‘Genes to Genomes: Forging ahead in the study of marine evolution” which we were happy

to help organize. (Special thanks to Dr. Michelle Gaither who was the lead

organizer and did all the heavy lifting.)

Soon after arriving we knew we were in paradise - an

expensive French paradise. My French is passable, but most of the locals we met

also spoke English as well their local Polynesian dialects. I always wanted to

come to Tahiti, not so much for its fishes or the beautiful teal-colored water,

but because I loved the history of Captains Cook and Bligh in this region; and because

of films like Marlon Brando’s Mutiny on

the Bounty.

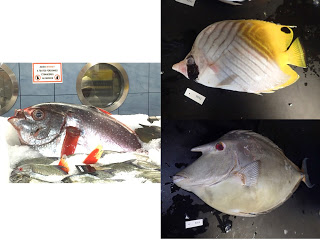

We went to the central fish market in Papeete around 5am the

first few mornings to see what we could get. We made nice collections of local

wrasses, goatfish, and unicornfish among other colorful, if odd-looking,

species. At the local grocery store we did come across a large specimen of an

Opah, or “Moonfish” which gained some notoriety recently as being “warm

blooded” – although some ichthyologists remain unconvinced. Sadly the specimen

was too big to collect, and already had it’s gills removed.

|

| Opah at market (left), butterflyfish (top), and unicornfish. |

We also traveled to the island of Moorea, which is about a

45min ferry ride from Tahiti. This island is home to, among other things, the

Gump Research Station run by UC Berkeley. The Gump helped us get our permits

but we were unfortunately unable to collect on Moorea. We had to settle for a

lovely day snorkeling in crystal clear water surrounded by lush green

mountains.

The conference started a few days after our arrival, and it

had about 500 attendees from around the world. Bill, Brant and I all spoke in

the first session of the first day after the plenaries. The Indo Pacific Fish

Conference is one of my favorites because I get to see many of the European,

Asian and African colleagues I often don’t see at conferences in North or South

America. Bill and I started several important collaborations that hopefully

will make for some fruitful publications over the next few months and years.

|

| Bill, Brant and I in Cook Bay, Moorea; Bill on stage presenting his talk. |

Although we didn’t hit the markets again during the meeting,

I did get to collect some introduced guppies. The extent of my freshwater fieldwork

was putting a bag down into a sewer off the main road in Tahiti and letting it

fill with water then pulling the bag out of the water to find that 50 individual

guppies had swam into the bag. Many of these specimens were mailed off to a

colleague studying the introduction of guppies around the world. He was very

happy to get individuals from this distant and isolated population.

I’ll spare

you more details about the fish conference and swimming with humpbacks (as I

did) and tiger sharks (as Bill did) and such, but rest assured this was no

vacation (although it obviously wasn’t all work either). The conference was a

great opportunity to talk about our work, including one collaboration that

recently yielded the cover of Systematic Biology (Chakrabarty & Faircloth

et al. 2017; left). That publication created some great opportunities to work with

other scientists interested in using genomic fragments like ultraconserved

elements in their phylogenetic studies of fishes.