Introduction

Sarcopterygii,

or the lobe-finned fishes, includes the coelacanths, lungfishes, fishes

involved in the transition to land, and all tetrapods (mammals,

amphibians, and reptiles [the birds, turtles, crocodiles, and squamates]). The

lobe-finned fishes are Devonian in age and the sister group to Actinopterygii,

or ray-finned fishes. Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii are nearly of equal size

(c. 30,000 spp. each). Actinopterygii is dominated by the teleost fishes, just as

Sarcopterygii is dominated by tetrapods. In this essay, the focus will be the

non-tetrapod members of Sarcopterygii, as I study fishes; however, it is worth

noting many of the skeletal elements and organ systems of tetrapods originated

in our aquatic sarcopterygian ancestors.

Had actinopterygians been the group to take charge as the vertebrate class

to dominate land, terrestrial vertebrates would look very different. It is likely that we would breathe through

our mouths alone or through our skin, be much smaller, and be hugging the

ground with soft rays holding us up against gravity rather than digits and

wrist bones. It was the advent of internal nostrils, or choanae, in aquatic

sarcopterygians that permitted us to breathe through our noses;

Sarcopterygii,

or the lobe-finned fishes, includes the coelacanths, lungfishes, fishes

involved in the transition to land, and all tetrapods (mammals,

amphibians, and reptiles [the birds, turtles, crocodiles, and squamates]). The

lobe-finned fishes are Devonian in age and the sister group to Actinopterygii,

or ray-finned fishes. Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii are nearly of equal size

(c. 30,000 spp. each). Actinopterygii is dominated by the teleost fishes, just as

Sarcopterygii is dominated by tetrapods. In this essay, the focus will be the

non-tetrapod members of Sarcopterygii, as I study fishes; however, it is worth

noting many of the skeletal elements and organ systems of tetrapods originated

in our aquatic sarcopterygian ancestors.

Had actinopterygians been the group to take charge as the vertebrate class

to dominate land, terrestrial vertebrates would look very different. It is likely that we would breathe through

our mouths alone or through our skin, be much smaller, and be hugging the

ground with soft rays holding us up against gravity rather than digits and

wrist bones. It was the advent of internal nostrils, or choanae, in aquatic

sarcopterygians that permitted us to breathe through our noses;  | |

| The rare ray-finned fish that can "walk" on land, the mudskipper. Image from http://www.studentsoftheworld.info/sites/animals/shadows.php |

Evolution and

Systematics

Coelacanths

belong to Actinistia (or Coelacanthimorpha), which has a long fossil record

(Mid-Devonian to Late Cretaceous) and that is species rich relative to the two

species extant today (83 valid fossil species in nine worldwide families).

Members of Actinistia are easily recognized by their tri-lobed diphycercal tail

(the vertebral column enters the middle lobe). Known as fossils from both marine

and freshwater deposits, they were thought to have gone extinct over 65 million

years ago, until a living species was discovered in 1938 to much fanfare. (The

discovery of both living species have spectacular stories behind them. See www.dinofish.com)

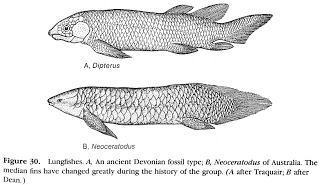

Lungfishes

are members of Dipnoi (themselves part of the larger group Porolepimorpha, largely

made up of extinct forms). This clade also evolved in Early Devonian freshwaters,

and is represented in the fossil record by more than 100 species in more than

50 genera. Their great fossil record of lungfishes was likely aided by their

ability to estivate. These fishes can protect themselves from drought by

building a mucous-mud cocoon. They enter periods of estivation that in modern

forms can last up to four years; many individuals in the past have expired

waiting for that next rain. These individuals and their cocoons make for spectacular,

if plaintive, fossils. From fossil forms, we see a trend toward the reduction

of bone (in the skull, scales, and fins). Unique plate-like grinding toothplates

easily help place extinct and extant forms as each other’s closest relatives.

Tetrapodomorphs are the intermediate

forms between the first tetrapods to conquer land and their piscine ancestors. They

are all limbed, extinct early Devonian forms, and air-breathers. They include Osteolepimorpha

(rhipidistians), Rhizodontiformes, and Elpistostegalians. It is the

tetrapodomorphs, in particular the Elpistostegalians (which includes Tiktallik) and not coelacanths or

lungfishes, that are the closest relatives to tetrapods.

Physical

Characteristics

Both lungfishes

and coelacanths can reach large sizes, approaching 2 m, although lungfishes are

much more slender bodied. Both groups have a number of derived features that

make each group unique. Coelacanths have a special rostral electroreceptive

organ, a vertebral column that is secondarily reduced, no maxilla, and an

intercranial joint found in many extinct fish lineages but no other living

species. Coelacanths have only external nostrils (no choanae) and a large fat-filled

gas bladder (no lung). These two latter features have been used by some authors

as evidence that these fishes are ancestral to lungfishes (which have both

lungs and choanae), but these primitive features may have more to do with the

current ecology of these animals than their biological history.

There are three extant families of

lungfishes: Ceratodontidae of Australia, Lepidosirenidae of South America, and

Protopteridae of Africa. Lungfishes are

easily recognized by their continuous rear fins that connect their dorsal,

caudal, and anal fins. The Australian Lungfish

(Neoceratodus forsteri) has a number

of pleisiomorphic morphological features that resemble fossil forms more so

than the other extant lineages. Instead of the tiny worm-like fins of the other

species, the Australian form has broad flat fins, large scales, and unpaired

lungs (versus small scales and paired lungs in the other taxa). Lungfishes

eat both plant and animal material, including ray-finned fishes and

invertebrates.

Reproductive

Biology

Coelacanths are ovoviviparous;

they retain eggs in the body cavity. The young hatch and develop internally. African

and South American lungfishes make nests where females lay eggs, and males

guard the nests. The Australian species lays its eggs on aquatic plants. The

African and South American forms have young with large external gills that

often cause them to be mistaken for salamanders.

Conservation

The

conservation status of most lungfishes is poorly known, but the Australian

lungfish is uncommon, confined to just four rivers in Queensland.

Among

coelacanths, Latimeria chalumnae is

found off the eastern to southeastern coast of Africa and around the Comoros

Islands and Madagascar, and L. menadoensis is only known from Sulawesi, Indonesia. Coelacanths are found at depths beyond the range of most artisanal

fishermen (150 to 253m), but accidental capture occurs frequently enough that

some estimate that as much as 5% of the adult population is captured annually. Coelacanths

aggregate and rest in caves; they may be limited by the number of these sites that

are available.

Significance to

Humans

As Moyle and

Cech state, “probably no single event in the history of ichthyology has

received more public attention than the discovery of the coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) in 1938.” The

discovery of this large, deep sea, limbed, fish-link-to-man made for fantastic

headlines. Lungfishes, too, have a

spectacular mix of features that make them popular aquarium fishes. Both

sarcopterygian fish clades are important to humans for their unique position on

the other side of the coin to the vertebrate transition to land.

References

Bemis, W.E,

Burggren, W.W., Kemp, N.E. (1987) The biology and evolution of lungfishes. Alan R. Liss, Inc., New

York.

Carroll,

R.L. 1996. Vertebrate paleontology and evolution. W.H. Freeman. New York.

Helfman,

G.S., Collette, B.B, Facey, D.E., Bowen, B.W. 2009. The diversity of fishes, 2nd

ed. Wiley Blackwell, West Sussex, UK.

Moyle, P.B.,

and Cech Jr., J.J. (2004) Fishes, an introduction to ichthyology, 5th edition. Prentice Hall, New

Jersey.

Musick,

J.A., Bruton, M.N., Balon, E.K. (1991) The biology of Latimeria chalumnae and evolution

of coelacanths. Environmental Biology of

Fishes 32, 1-435.